Last week, for the anniversary of the Battle of Second Bull Run, I led a leadership development event where we focused on leading through change.

Our group spent the majority of the time assessing Major General John Pope’s decisions when standing up the newly created Army of Virginia in 1862. His infamous “Address to the Army” was meant to inspire boldness, but instead it alienated his soldiers and sowed division.

It’s a powerful reminder that tone matters as much as vision—especially in periods of transition. Leaders often feel pressure to assert authority quickly, but real success depends on building trust and respecting the experiences of those you lead.

If you are interested in collaborating on a similar leadership event, or one-on-one coaching, reach out to me at [email protected]

Setting the Stage: A New Army for a New Crisis

By midsummer 1862, the Union cause was in a perilous moment. The Army of the Potomac under George B. McClellan had stalled outside Richmond during the Peninsula Campaign. President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, alarmed by the Confederate counteroffensive under Robert E. Lee, needed a fresh force to shield Washington and reassert Union initiative in Virginia. Thus was born the Army of Virginia, cobbled together from disparate corps and regional commands in northern Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley, and western Virginia.

The logic was both strategic and political. Washington, threatened repeatedly in 1861–62, needed a dedicated force to secure its approaches. But equally important was a shift in leadership style. McClellan, once the Union’s rising star, had alienated the administration with his cautious battlefield performance and Democratic political leanings. Lincoln wanted a general who would fight aggressively and embody the administration’s firmer war policy. Enter Major General John Pope.

Why Pope?

Pope’s selection was as much about politics as it was about military merit. He had enjoyed success in the western theater, most notably capturing Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River in early 1862, a victory that earned him national attention. More importantly, he was a vocal proponent of “hard war”—the emerging belief that the Confederacy’s will could be broken only by harsher measures against its resources and population. In contrast to McClellan’s deference toward Southern property and civilians, Pope promised a sterner brand of war.

For Lincoln and Stanton, Pope represented a clean break. He was a Republican, he was outspoken, and he was willing to test harsher policies. But his very personality—a brusque, confident manner often read as arrogance—set the stage for conflict not only with Confederates but within his own ranks.

Pope’s Address to His Army

When Pope assumed command in July 1862, he issued a (in)famous “Address to the Army of Virginia.” It was less a measured introduction than a gauntlet thrown down before his new command.

“I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary, and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.”

“I presume that I have been called here to pursue the same system, and to lead you against the enemy. It is my purpose to do so, and that speedily.”

“Let us look before, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.”

“I shall expect you to overcome all resistance. I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases which I am sorry to find much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of ‘taking strong positions and holding them’… and of ‘retreating to lines of defense.’ Let us discard such ideas.”

The desired effect was clear: Pope wanted to inspire confidence, energize his soldiers, and project the image of a decisive, no-nonsense commander. He hoped to distance himself from McClellan’s caution and instill an offensive spirit.

The Actual Impact: A Divided Force

Yet the speech had the opposite result. Many officers of the Army of Virginia, especially career regulars, bristled at Pope’s words. They read his comparisons as insults, dismissing the hard campaigning they had already endured in the East. Instead of bonding his army, Pope alienated it. His tone—mocking, dismissive, and self-aggrandizing—made him appear arrogant. McClellan’s loyalists, still commanding corps and brigades in the region, felt personally slighted and would never fully support him.

In essence, Pope’s opening message squandered a crucial chance to unify a newly assembled army. What could have been a rallying cry became a wedge. When Pope faced Lee at the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August 1862, those divisions contributed to confusion, poor coordination, and eventual defeat.

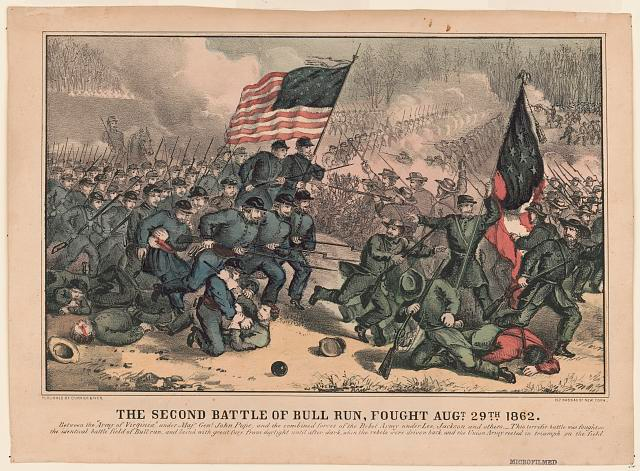

Consequence: The Second Battle of Bull Run

From August 28–30, 1862, Pope’s Army of Virginia collided with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in a complex series of maneuvers and assaults near Manassas—on the same ground where the war’s first major battle had unfolded. Lee’s bold use of Stonewall Jackson’s wing to seize and hold a strong defensive position, coupled with James Longstreet’s massive counterattack, crushed Pope’s army. The Union retreat was disorderly, the loss humiliating.

While strategic mistakes on the battlefield sealed Pope’s fate, the seeds of his downfall had been planted earlier. An army suspicious of its leader, led by a man whose rhetoric had estranged rather than inspired, entered the campaign without cohesion or trust.

Leadership in a Period of Change: Lessons from Pope’s Message

John Pope’s welcome address offers a timeless lesson about leadership during moments of organizational change: tone matters as much as vision.

- Desired Effect: Pope wanted to shake his soldiers from complacency and set a new, aggressive course.

- Actual Impact: By belittling their past and comparing them unfavorably to other forces, he alienated those whose loyalty he most needed.

In times of transition—whether in war, business, or community life—leaders often feel pressure to assert authority quickly. Pope’s example shows that while boldness has its place, effective leadership requires empathy and respect for the experiences of those you lead. Change cannot be imposed with contempt; it must be built on trust.

The Second Battle of Bull Run reminds us that campaigns are fought not only with strategy and numbers, but also with morale and unity. Pope’s failure to recognize that truth left his army—and his reputation—broken in the fields of Virginia.