Beginning at nightfall on July 13, 1863, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began crossing the Potomac River near Falling Waters, Maryland, thanks to a hastily rebuilt pontoon bridge and the river finally dropping below flood stage. This marked the end of a six-week campaign that began on June 3, when Lee started his movement out of Fredericksburg, and concluded on July 14, when the last Confederate troops slipped back into Virginia.

While there are myriad lessons to explore at Gettysburg, in my leadership development events, a few of my favorites come from examining Lee and Meade’s decision-making and movements after the battle. One of those themes centers on each commander’s assessment of their own condition and that of their enemy (or in Sun Tzu’s terms: “Know thyself and know thy enemy”). It’s a valuable compare-and-contrast exercise.

How well did Lee “know himself” after the rapid changes in force structure and leadership that occurred following the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1–3, 1863)? And did he truly recognize the strengths of the Army of the Potomac following Joseph Hooker’s reforms and the arrival of new senior leadership?

For George Meade, who had been in command for just over two weeks at the time of the battle, how well could he know himself (both as an army commander and his force with three new corps commanders in place due to casualties at Gettysburg)? And how did Meade assess Lee’s condition in the aftermath of the fight?

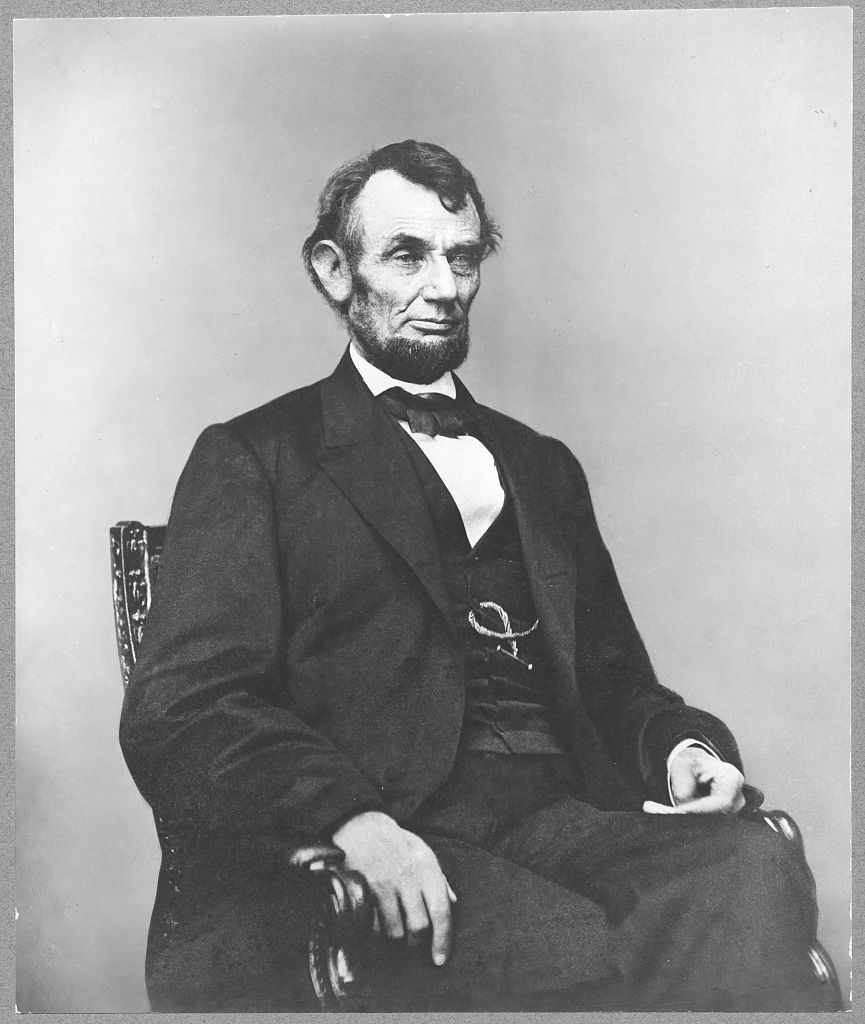

President Abraham Lincoln certainly offered his own assessment of both armies—and their commanders—in a letter he penned to Meade but never sent. Lincoln wrote:

“I had been oppressed nearly ever since the battles at Gettysburg, by what appeared to be evidences that [you] were not seeking a collision with the enemy, but were trying to get him across the river without another battle.”

He continued:

“You fought and beat the enemy at Gettysburg; and, …, his loss was as great as yours— He retreated; and you did not…”

But Lincoln’s disappointment did not stop there:

“Again, my dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape— He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war— As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely… Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it—”

If you’re interested in exploring these or other leadership topics, reach out to me!

? https://2gsx.com/contact

? [email protected]

Share this post: